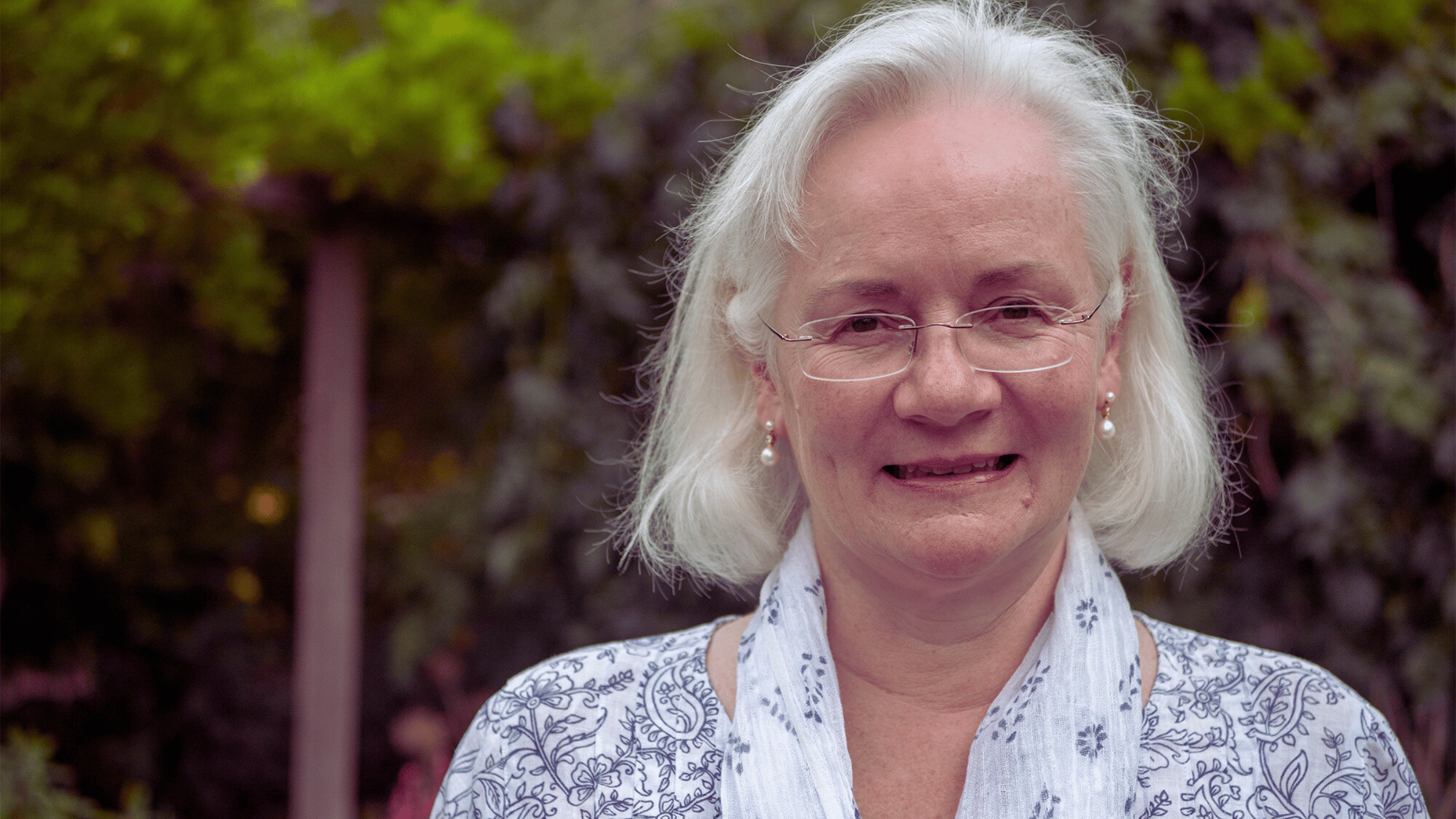

Sarah Girling is our Diocesan Pastoral Secretary and oversees the process of church closure for the diocese; here she explains why we prefer not to close churches and how closure happens, if and when it is needed

I’m the person at the diocese responsible for taking churches through the process of closure when that is needed. You would have thought that this is a sad job to have; in fact I am constantly amazed by the resilience and imagination of communities faced with this difficult decision. I’m very happy to be able to take this opportunity to talk a bit more about what the process involves, as it’s an area rich in misunderstandings and myths, and also to tell you about places where people have successfully navigated the process and have come out peacefully at the other end.

The first myth to bust is that I need to tell you that diocesan policy is pretty firmly against church closure. First, we are in the business of open churches, not closed churches. Second, open churches are owned locally, by the incumbent and PCC, not by the diocese; the diocese can’t actually impose a church closure on a PCC that wants to keep the church open. The decision to close a church can only be taken by the Church Commissioners. It’s not a decision for the diocese, the PCC, the incumbent or even the Bishop. Thirdly, and more practically, it usually costs the diocese quite a bit of money to close a church, so we’d rather not.

The closure of a much-loved church is something that nobody really wants to contemplate. There are often strong feelings of sadness, responsibility, guilt, and “not on my watch”. At the same time the background can be one of a smaller and smaller pool of people taking on responsibility for an important historic building and the myriad bits of administration that go with being a PCC. Considering the possibility of closure can be a response to a number of different things. It could be a Quinquennial report with some scary numbers at the end for the likely cost of repairs needed; it could be that nobody on the PCC is able to continue, and nobody else has come forward; it could be the end of a long, slow decline in local population over the course of a century or two.

The first step is always to engage as fully as possible with the local community, more widely than just the regular congregation, and ensure that they understand that they are at the “use it or lose it” stage. It’s important to understand who else might be out there and what skills they have to offer. I’m always happy to come and attend PCC and public meetings to ensure people understand what the alternatives are, as we would all prefer to keep our churches open. I’ve been to quite a few such meetings where the PCC has reached out to the wider community, and as a result of their efforts they now have a rejuvenated PCC, and closure is off the agenda.

Another possibility might be to unite with one or more neighbouring parishes and have a two-church parish (or more) with a single PCC, to reduce the administrative load; or alternatively to set up a joint council for two or more parishes. Again, I’m always happy to talk about the options for this sort of reorganisation, and your incumbent and archdeacon will help too.

If everything that you and the diocesan team can think of has been tried without any luck, it may be that there is no realistic alternative to closure. So what does that actually entail?

The process is started by the PCC requesting the diocese to start a consultation on closure. Consultees include local clergy and PCCs, patrons, rural dean and archdeacon, local parish council, ward councillor and county planning department, and Historic England/Cadw. I run the first round of the consultation and the Commissioners run the second. It does not cost the PCC anything. Anyone can comment on the consultation – it is not limited to the official consultees. If there are objections, the Commissioners will make a decision as to whether the closure will go ahead or not.

The church remains open during the consultations and everything, including services, continues as normal unless and until the church is finally closed. If the church closes, there will be time for a final thanksgiving service beforehand.

It is quite common for the first question about a possible closure to be whether people can still be buried in the churchyard. The answer is usually yes, although it will depend on local details. A church closure usually only affects the building itself. The churchyard (assuming it is open for burials) remains open and in the care of the PCC, even if the church building closes.

So in a case where closure does go ahead, what happens next?

Responsibility for the church building, and for its insurance and some repair, moves, on the date of closure, from the PCC to the diocese. It is the task of the diocese to find a “suitable alternative use” for the building. In some cases it may be that there is already a suitable use in prospect. For example, where a parish church was originally an estate church, associated with the local manor house, it may be that the owners of the manor house are willing to take on responsibility for the building to preserve it for the future, or use it as a private chapel. In such cases it may be possible, with the Bishop’s permission, to continue to hold occasional services there.

In some other cases, where the church building is listed grade I and of national importance, it may be possible for the church to be vested in the Churches Conservation Trust. The CCT is a statutory body set up to preserve such church buildings. Like most bodies, however, the CCT’s budget is limited so this cannot be guaranteed. The Friends of Friendless Churches is a similar body which is dedicated to the preservation of closed church buildings where no other buyer is likely to be found.

If none of these options are available, the usual course will be to put the church on the open market to see what interest there may be. It is not easy to find buyers for these buildings; they may be priceless in spiritual, community and heritage terms, but they do not usually have a high commercial value. This is both because they usually need quite a bit in the way of repairs, and because nearly all our churches are highly listed and so there are considerable restrictions on what can be done with them. And of course they are usually surrounded by an open graveyard, which doesn’t appeal to everyone.

We are also not permitted by church law to sell closed churches on a speculative basis to people who haven’t decided what to do with them. This means that any prospective buyer has to get planning permission and listed building consent for specific plans, agreed with the Commissioners, before they can complete the purchase. The local planning authority usually has a fairly long list of its own requirements as well, and in many cases prefers a use where public access will still be possible, especially where the interior of the building is historically important. There is also another church consultation on the proposed use of the building, which runs along similar lines to the original consultation on closure. Again, anyone can respond to this consultation on the proposed use. All this does make it harder to sell closed churches. But it also provides considerable comfort to the local community, as they have the right to have their views taken into account on the future use of the building, both in the planning process and in the church consultation.

The future use of the building is controlled and protected permanently after the disposal, because the Church Commissioners will insist upon strict covenants as to how the building is used, and to protect and preserve its important features and contents. Since nearly all of our church buildings are listed, the building also continues to be protected by that designation. The final decision on any disposal is, again, made by the Commissioners.

All this means that it can take quite a number of years to find a satisfactory solution for a closed church building. You’ll probably therefore begin to understand why the diocese isn’t very keen on closing churches!

I’d like to end with a success story. We’re all enormously grateful to the Friends of Friendless Churches for taking on a number of our closed church buildings, most recently the beautiful little church of St James, Llangua. The story of the rescue of St James’ church is beguiling and inspiring, and you can find it on the Friends’ website.

Do read the wonderful scrapbook of the rescue project – you’ll find the link at the bottom of the webpage referred to above – and find out about how a rare roof moss helped track down some local criminals. The church building is now open for visitors every day, so if you’re ever on the road between Hereford and Abergavenny, stop and have a look. It’s a wonderful place, safe now for a few more centuries. It’s no longer a parish church, but it remains a sacred space. And if the story makes you feel inclined to support the Friends of Friendless Churches, please do so, in the knowledge that you’ll almost certainly be helping save some church buildings in this diocese.

– ENDS –